Will China’s new visa targeting STEM talents give it an edge over the world?

SCMP | September 09 , 2025K visa meant to help young foreigners find their professional footing can only succeed with effective policy support, analysts say

Rahdar Hussain Afridi, a Pakistani national studying for a PhD in robotics at Peking University, had been worried about whether he could stay on after graduating in January.

He hopes to secure a job in China, but the recruitment process can take a while and his student visa, which might expire soon after graduation, does not come with a work permit.

China’s newly introduced “young talent” K visa for STEM professionals has brought him “great relief”.

“I am really happy to hear about this visa,” said Afridi, 29. “I have been living in China for the past six years, and I am one visa away from being asked to leave. I have been living with such huge uncertainty.”

Taking effect on October 1, the new visa category will offer greater flexibility and fewer barriers to global professionals in the fields of science, technology, engineering and mathematics. Observers said it signalled a shift in China’s immigration policy and a strategic move to bolster innovation and competitiveness in its hi-tech sectors.

The strategy also aims to capitalise on a more restrictive immigration climate elsewhere in the world, particularly in the United States, according to analysts.

But whether the plan would work remained to be seen, they cautioned, while calling for effective policy support.

Unveiled in early August by the State Council, China’s cabinet, the “K-type visa only has specific requirements regarding age, educational background, or work experience, and does not require a domestic employer or inviting entity”, according to state broadcaster CCTV.

Chinese diplomatic missions would post more details about the visa’s requirements, it said.

Wang Huiyao, founder of the Beijing-based think tank Centre for China and Globalisation(CCG), said the K visa’s introduction marked “a major shift in China’s immigration policy”.

“Previously, the focus was on attracting overseas Chinese for multinational corporations or family reunifications. Now, there is a clear emphasis on tech and innovative talent.”

In addition to targeting overseas Chinese communities, the policy would appeal to those who went to the US or Europe, Wang said, including young people from both developed and developing countries, especially India, Japan and South Korea.

He called the K visa a well-matched solution for China, given the country’s tech transformation, need for talent and “unparalleled” advantages.

According to Wang, China’s strengths include its vast market, extensive talent network, rapidly advancing universities, and thousands of entrepreneurial and industrial tech parks.

“I believe it’s only a matter of time before a wave of talent begins flowing into China, and this trend will continue to grow.”

“The US is becoming more closed off, while China is becoming more open,” he added, describing the new visa as an extension of Beijing’s post-pandemic push to make it easier for foreigners to visit the country.

China’s visa-free entry scheme has yielded substantial results.

In the first half of this year, about 13.6 million foreigners visited China under the scheme, which started with six countries in 2023 and expanded to more than 70 countries in July. The 2025 figure represented a year-on-year increase of nearly 54 per cent.

Liu Hong, a professor of public policy and global affairs at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, expects the US administration’s tightening grip on immigration to help drive foreigners to China.

However, he said China’s K visa should not be viewed as a direct competitor or an alternative to the US H-1B visa, which is a work visa requiring employer sponsorship.

The H-1B visa had higher requirements in terms of “educational credentials, work experience and minimum salary, and the potential applicant pool is much bigger”.

In contrast, most K visa applicants were likely to be overseas second-generation Chinese engaged in tech and science fields, along with young professionals from the West and the Global South, Liu said.

The Donald Trump administration has significantly tightened US immigration policy this year through executive actions and new regulations, in a drive to remove unlawful migrants.

Last month, for instance, the Trump administration proposed a rule to limit the validity of foreign student visas.

Also in August, Republican Senator Mike Lee suggested a pause on H-1B visas, many of which are held by highly skilled workers from India.

Liu said another major advantage in China was policy incentives from both the central and local governments, which prioritised talent in promoting innovation and economic development.

“Although China has experienced economic slowdown over the past couple of years, the prospect for growth remains positive,” he said.

For Afridi at Peking University, financial considerations helped to shape his decision to study in China.

The US was too expensive and high-ranking European universities were unlikely to offer scholarships, he recalled. Meanwhile, he found that salary offers in Singapore and South Korea were less competitive compared to those for top talent in China.

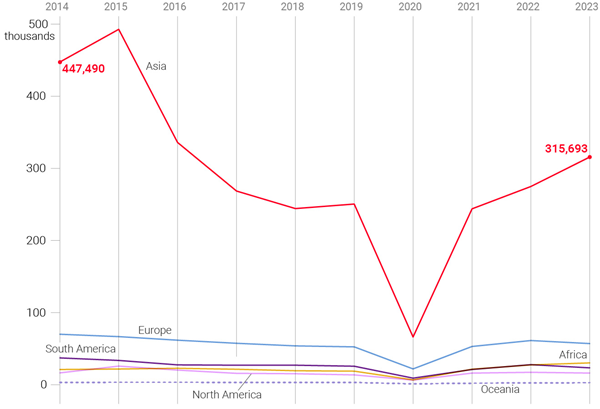

Foreign student visa issuances to the US

“So, I chose China,” Afridi said. “At that time, my elder brother told me that the future would be in China. What he meant was that a future without China is impossible, so it’s better that you go and stay there.”

However, David Zweig, professor emeritus of social science at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, cautioned that mainland of China’s research environment and economic climate might not be as welcoming as the new visa policy suggested.

Intense competition and complex interpersonal dynamics were two major challenges in attracting and retaining foreign research talent, Zweig said.

Chinese academia has a history of competition between scholars with overseas education and those without, he added.

This tension was rekindled following China’s launch of the Thousand Talents Plan in 2008. The scheme recruited expatriate scientists and sparked fresh competition between the returnees and local leaders lacking extensive international experience.

An influx of new foreign talent through the K visa could intensify this competition, said Zweig, with locals possibly questioning what the foreigners had accomplished or “proven” to deserve special treatment and benefits.

According to Liu, robust selection standards and effective institutionalisation of China’s talent strategy are critical for the K visa programme to succeed – covering recruitment, nurturing, management and appraisal.

“It is also important to ensure that China’s own university graduates, who are facing significant challenges in finding employment, are not being put at a disadvantage,” he said.

Wang at the Centre for China and Globalisation called for the publication of data on permanent residence permits issued to foreigners staying long-term as well as on visa approvals for international students – to boost transparency on the number granted each year.

“Visibility is crucial,” he said.

From SCMP, 2025-9-9

Recommended Articles

-

KNA | Global trade, U.S.-China tensions, AI regulation

-

[Research Features] China’s role in a sustainable post-pandemic globalization

-

Wang Huiyao: China is not a threat to the international community - the world can benefit through China’s development

-

Wang Huiyao in dialogue with Lawrence H. Summers

-

Straits Times Interviews Wang Huiyao on China-India Relations