How coronavirus exposed the collapse of global leadership

Nikkei Asian Review | April 14 , 2020The pandemic called for coordinated action. No one answered

Instead of crafting a global plan, the U.S. and China — the two world powers best suited to lead a coronavirus response — have sniped at one another from the sidelines. © Reuters

SINGAPORE — As car crash interviews go, Bruce Aylward’s was excruciating and revealing in equal measure. In late March, Alyward, a Canadian epidemiologist and adviser to the World Health Organization, was asked by Radio Television Hong Kong reporter Yvonne Tong whether Taiwan would continue to be denied WHO membership, given longstanding objections from China. At first he stalled, claiming not to be able to hear the question. Then his connection went down. Then Aylward returned to the call and declined to answer at all.

The clip went viral in part for its awkwardness, but also because it illustrated a deeper truth — namely that geopolitical fissures, and strained relations between the U.S. and China in particular, have badly undermined early international efforts to respond to the coronavirus pandemic. And while that suspicion starts with the WHO, it does not end there.

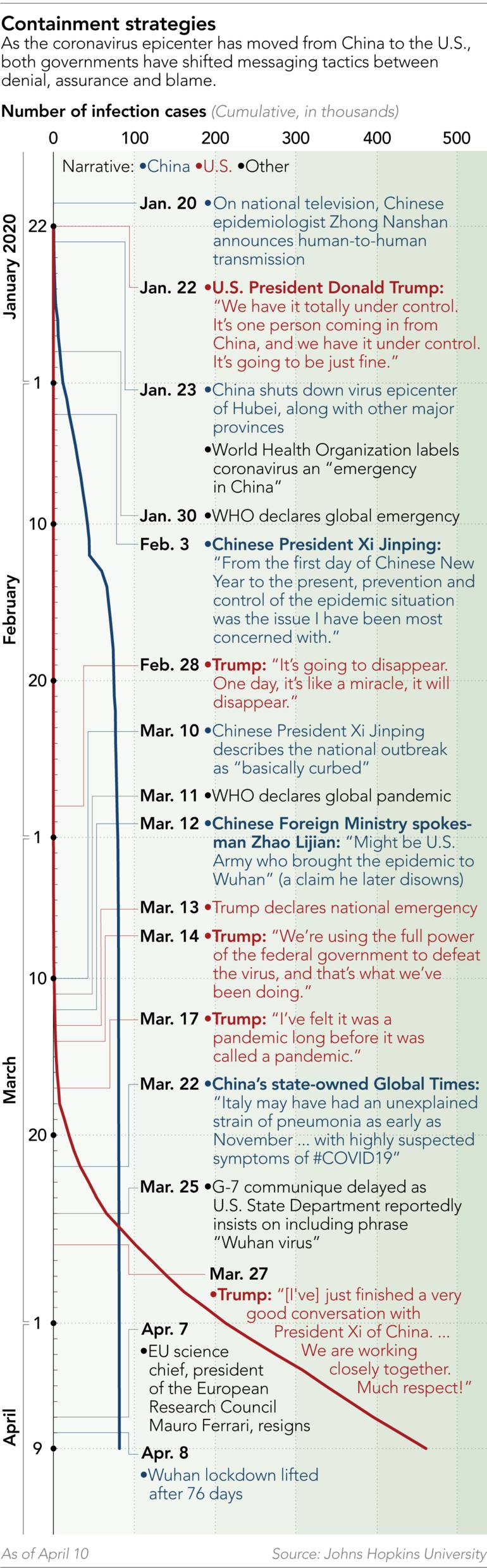

Amid much finger-pointing between Beijing and Washington, many in the West now claim the outbreak grew out of control because the global health body accepted reassurances from Beijing about the severity of its early stages in Wuhan. “The @WHO is an accomplice to China’s massive coverup of Covid19,” as former U.S. National Security Adviser John Bolton said on Twitter recently. As if to underline the severity of this breakdown of trust, on April 14 President Donald Trump drew widespread criticism for announcing plans to halt U.S. funding to the WHO entirely, accusing the body of spreading Chinese “disinformation” about the pandemic.

Chinese officials had attempted to cast doubt on the origins of the virus, with Foreign Ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian tweeting on March 12 that it “might be U.S. Army who brought the epidemic to Wuhan,” before later partially rowing back on the same claim.

Such back-and-forth accusations are just a small part of wider worries about a slow-moving response from the international institutions that might otherwise have been expected to drive forward the world’s fightback, most obviously via the large global economies comprising the Group of 20.

Bruce Aylward, International team lead for the WHO-China joint mission on COVID-19 coronavirus attends a news conference after his trip to China at the World Health Organization in Geneva in February. © Reuters

A little more than a decade ago, G-20 leaders gathered in London, along with heads of international bodies like the International Monetary Fund, to stop a worsening financial crisis turning into a global depression. Now, facing what Kristalina Georgieva, IMF managing director, describes as a crisis “way worse” than 2008, those same institutions have faltered. And rather than crafting a new global plan, the two global powers best suited to lead a response, the U.S. and China, have sniped at one another from the sidelines.

“On any measure, the global response, both on public health and economic policy, has been unacceptably slow and disorganized,” says Kevin Rudd, who was Australian Prime Minister during the global financial crisis and deeply involved in the international response. While national governments have introduced unprecedented measures to slow the disease and prepare for its economic impact, international action has been held back by squabbling and limited leadership. “The bottom line is that in 2008 we built a machine to manage a crisis just like this one. But, so far, no one has stepped up to drive that machine.”

Containing a crisis

At one level, this weak response is easy to understand: Leaders in the U.S. and China, in common with almost every other major global economy, are solely preoccupied with crisis management. As the global death toll rises over 100,000, individual leaders have scrambled to introduce lockdowns, protect overburdened health services and roll out bold fiscal measures to protect vulnerable workers. Some global bodies have acted too, with the World Bank pledging to spend $160 billion over the next year or so, and plans for extra spending from the IMF, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and others.

Chinese airplanes drop emergency goods in Phnom Penh, Cambodia.

When G-20 leaders met for a virtual summit in late March, their communique committed to pushing $5 trillion into the global economy, roughly five times the amount the group committed at its London meeting in 2009, led by then-British Prime Minister Gordon Brown. “$5 trillion is a lot,” says Bert Hofman, former head of the World Bank in China and now director of the Singapore-based East Asian Institute at the National University of Singapore. “It isn’t just throwing the kitchen sink at the problem. It is throwing the whole kitchen.”

Yet, for all its impressive size, the G-20’s top-line announcement consisted merely of measures previously announced from national governments. In a host of other areas requiring global action, there was less to go on. International travel and trade restrictions continue to be introduced without coordination, let alone consideration of how they might ultimately be lifted. Attempts to fund a vaccine, while urgent, have been piecemeal. Major oil-producing nations did manage to strike a deal to cut production by 10 million barrels a day, potentially ending a damaging price war between Saudi Arabia and Russia – although it remains unclear if the G-20, which backs the deal, will be able to ensure it is actually delivered.

Elsewhere, central bank policy easing and emergency national fiscal spending plans have been rolled out independently from one other. While substantial monetary policy measures have been announced by the Federal Reserve and others, there are clear limits to its effectiveness in an environment where interest rates in most major advanced economies are already close to zero.

Facing unprecedented declines in international commerce, which the World Trade Organization says could fall by as much as a third over the next year, global leaders have also failed to agree any limits on damaging protectionist measures in areas like food and medical equipment, as they did during the 2009 crisis. This opens the way for a wave of further new tariffs and other barriers, as well as potentially worsening existing trade tensions between the U.S. and China.

Nor has there been much in the way of measures to help nations in regions like South Asia and Latin America, whose large populations and creaky health systems now risk severe outbreaks. Facing outflows of capital, emerging markets like India require access to funds with no strings attached, suggests economist Arvind Subramanian, the country’s former chief economic adviser.

U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo addresses the daily coronavirus taskforce briefing at the White House, watched by President Donald Trump. © Reuters

“Developing nations need cheap money, quick money and unconditional money, and they need it now,” he says. “The big international institutions haven’t got to that level yet, because there has not been much leadership from the big guys.”

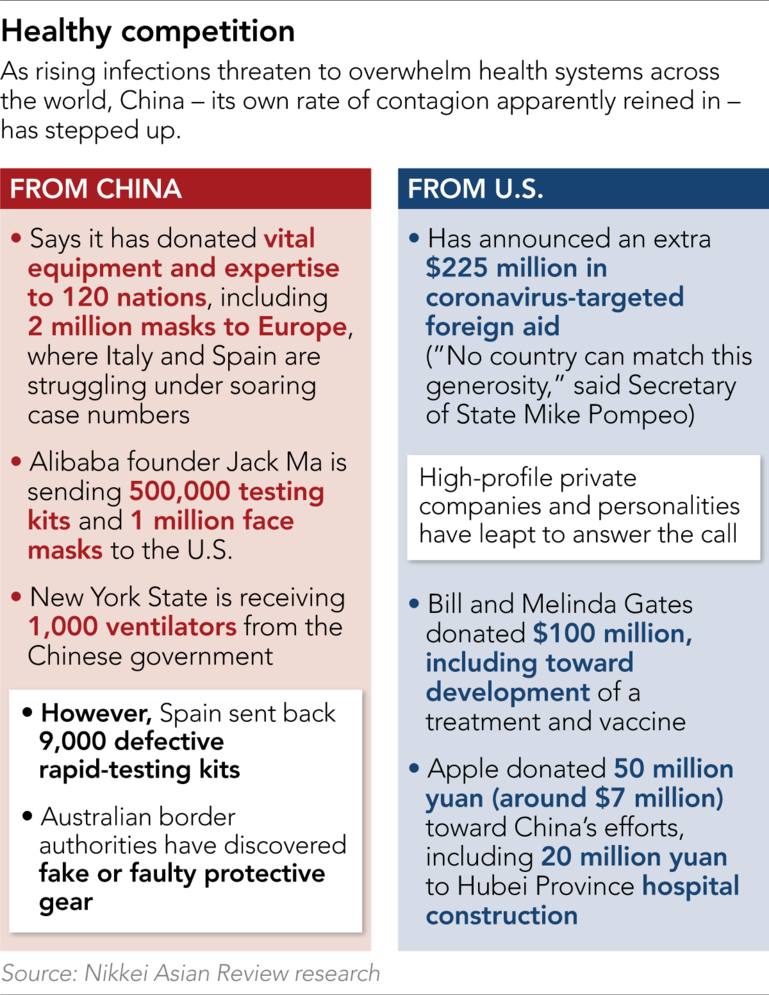

In the place of coordinated measures, recent coronavirus diplomacy has all-too-often mixed passive aggression with competition for resources, especially with attempts to source badly needed medical equipment. “Frankly, it has been a case of getting your hands on whatever you can before the others do,” says one Asia-based western diplomat. Even seemingly well-meaning attempts to help come with political overtones. In early April Russia landed a military plane in New York filled with emergency supplies, in what was widely viewed as an exercise in goading, masquerading as a mercy mission from President Vladimir Putin.

Some of these leadership problems stem from the G-20 itself. Current chair Saudi Arabia did manage to pull a virtual meeting together on short notice, but its next full leaders’ meeting is not scheduled until November. That the group is being led from Riyadh is hardly helping, given Saudi Arabia’s scant experience coordinating such bodies, and the fact that its leader Mohammed bin Salman is still struggling for legitimacy in the aftermath of 2018’s murder of dissident journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

More important have been ongoing tensions between the U.S. and China, which makes attempts at international coordination especially problematic. U.S. President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping talked on the phone in late March, releasing cordial statements pledging to work together, even though evidence of such cooperation is hard to find. Foreign ministers from the G-7 group of advanced economies failed even to sign on a communique at their last meeting, reportedly because the U.S. State Department insisted on including the phrase “Wuhan virus” — although in a subsequent interview with Nikkei, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo denied that had been the reason for talks breaking down.

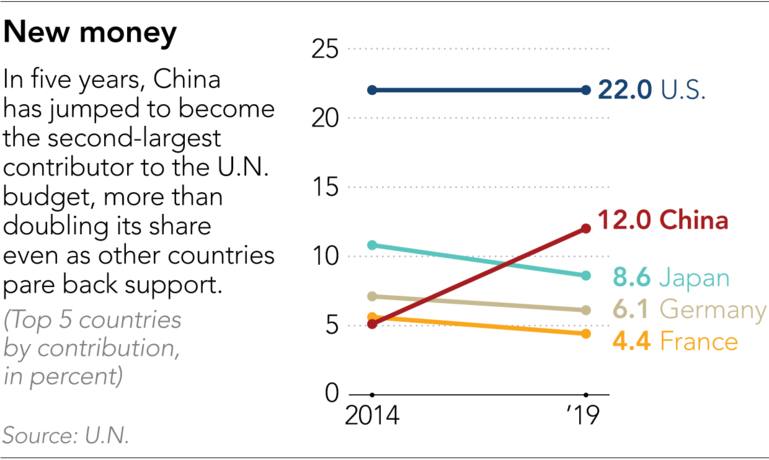

Before announcing its funding suspension, On April 7 President Donald Trump had first threatened to stop funding the WHO, implicitly accusing the organisation of limiting its pandemic response for fear of angering China, its second-largest source of funding after the U.S. Those who know the WHO well say Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO director-general, is in effect caught in a wider quagmire caused by geopolitics rather than the spread of disease, given fundamental disagreements between his most important members.

Meanwhile, any increase in Chinese influence stems at least in part from a vacuum at the top, given the way the U.S. has declined to adopt its traditional role as a leader at the WHO and other similar institutions, and bear the costs which came along with this. “It’s a political organisation, and its member states, especially those that give it a lot of money, are powerful,” one former WHO official told the Nikkei Asian Review. “It’s hard for the leadership in Geneva to act without support from countries like the U.S., Japan or China.”

Most global institutions have operated since the end of the Cold War with an implicit assumption of American leadership. As recently as 2014, the U.S. led a response to West Africa’s Ebola outbreak, as it did during the financial crisis and myriad other moments of international turbulence. The coronavirus crisis has only made it clearer that, under Trump, the U.S. shows far less interest in taking up that role, even within the G-20. Founded only in 1999, the grouping at first restricted itself to gatherings of finance and foreign ministers, until the financial crisis made it the forum of choice for international leaders. “Both [George W.] Bush and [Barack] Obama made the G-20 work in the middle of that crisis,” says Kevin Rudd. “Trump has chosen not to make it work this time.”

U.S. First Lady Melania Trump greets children by shaking their hands during a state visit to India on Feb. 25. © Reuters

Although Trump’s antipathy toward multilateralism is well known, China has also proved unwilling to play anything approaching a full global coordinating role. At one level, the ongoing crisis seems to provide President Xi Jinping with an ideal opportunity to demonstrate China’s capacity for global leadership. And as its own outbreak in Wuhan is brought under control, Xi has indeed been active abroad, sending masks and protective equipment to more than 100 countries — in particular to those with whom it has friendly relations via initiatives like its Belt and Road infrastructure program.

Yet here China faces constraints too. Its own internal pandemic troubles are far from over, with a potential second wave of infections likely as restrictions are released. Communist Party leaders remain anxious about domestic public opinion, limiting their ability to send funds abroad that could be used to fund recovery at home. More to the point, China has never conceived of itself as supplanting the historic role played by the U.S., suggests former Singaporean diplomat Kishore Mahbubani, and author of “Has China Won?”, a new book on Sino-U.S. relations. “China has no desire to run the world in the way the Americans or the West have done,” he says. “The Chinese are happy to play their part, but most of all want to take care of China.”

‘Poorer, smaller world’

What might a more coherent international response look like? And, given all these many constraints, how could it actually happen? In the aftermath of the lackluster virtual G-20 meeting in March, former British Prime Minister Gordon Brown began to think through measures international leaders could consider, and in turn how to apply pressure to promote them. He began emailing and calling other former world leaders, many of whom happened to be stuck at home, locked down in their own countries.

Initial conversations with the likes of Kevin Rudd and former Spanish Prime Minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero developed quickly into a mini-manifesto for global pandemic cooperation.

“Gordon’s idea was to gather together some of the group that had been around in 2008, but it snowballed from there,” says Tom Fletcher, a former Downing Street aide and British diplomat now based in the United Arab Emirates, who worked as part of an impromptu team to coordinate the signatures. The results were published as an open letter to G-20 leaders on April 6, signed by 165 former world leaders, international bureaucrats and charity heads.

Brown’s central proposal was to create a new $193 billion global fund, as part of a renewed international push to cope with the social and financial fallout from the pandemic, which would require “funding far beyond the current capacity of our existing international institutions.” Eight billion dollars would be set aside to fund research into a vaccine, in part by boosting the WHO’s budget. A larger slice of $35 billion would provide emergency health supplies to countries struggling to source their own. The balance would patch up social safety nets in vulnerable emerging economies, helping to provide unemployment payments and other badly needed support — all as part of a broader battle to stop the epicenter of the epidemic moving from rich advanced economies to poorer emerging nations in Asia and Africa.

Brown’s proposals floated a host of other ideas, many focused on freeing up existing international institutions to pump more money into the global financial system, for instance by expanding currency swap arrangements for struggling emerging markets.

Around $600 billion could come via the IMF’s system of Special Drawing Rights, a kind of virtual currency made up of other currencies, while rules governing lending from bodies like the IMF, World Bank and AIIB could be relaxed, especially if their major shareholders provided more capital. “Our aim should be to prevent a liquidity crisis turning into a solvency crisis, and a global recession becoming a global depression,” the letter said.

Masked workers disinfect the podium before the White House’s daily coronavirus taskforce briefing. © Reuters

There are reasons to think such measures could indeed be possible, Fletcher suggests. Even without clear leadership from the U.S. or China, the G-20’s machine can be made to function if a handful of credible leaders begin to focus on what he describes as the “hard graft of cajoling, bargaining and banging heads behind the scenes.” As national outbreaks are gradually wrestled under control, the heads of some major economies might gradually find space to grapple with the pandemic’s coming stages, where sustained international cooperation is likely to be even more important.

Potential candidates for that leadership role could include President Emmanuel Macron of France or Prime Minister Shinzo Abe of Japan, Fletcher suggests, with Japan especially well-placed given its role as part of the G-20 “troika” — a three-member country committee within the G-20 compromising the previous, current and next summit presidents.

Leaders from countries that have performed well in the early stages of the crisis, including Germany, South Korea, and Singapore, which attends G-20 summits as an observer, could be influential too. Bodies like the IMF and World Bank could play a more aggressive role too, potentially unencumbered by constraints from their more powerful members, suggests Arvind Subramanian: “In this environment national leaders in crisis management mode are much more likely to say ‘fine, great, that sounds good, go ahead’ rather than blocking bold ideas.”

International cooperation, largely absent during the crisis, is likely to become even more important as the pandemic develops. © Reuters

Crafting international agreements takes time. The London G-20 meeting in 2009 took place more than half a year after the collapse of Lehman Brothers, while the present COVID-19 crisis is barely three months old. Although a full G-20 meeting is not due to take place until November, further virtual meetings or ad-hoc groupings are likely in the interim, such as the meeting of G-20 oil ministers which took place on April 10, to try and hammer out a deal to cut production.

It also remains possible that the U.S. and China could step up. Although skeptical of multilateralism, Trump faces a tight election battle, and could eventually see some political advantage in fashioning a more prominent global role.

China has clear economic self-interests in restarting its mothballed export-driven economy too, which is unlikely to happen until the many countries that buy its goods have brought their own outbreaks under control. Wang Huiyao, president of the Beijing-based Center for China and Globalization(CCG), says that even if China is unlikely to head an international response, its leadership is likely to work cooperatively with others to fashion one.

“China does not want the leading role, but it wants an active role,” he says. “China’s actions will be especially pivotal in ensuring global trade value chains are not totally crashed.”

Self-interest of this kind is far from guaranteed, however. U.S.-China cooperation has been almost entirely absent during the early stages of this crisis, which now seems as likely to deepen the two nation’s divisions as it is to bring them together. The aftermath of the global financial crisis suggests countries facing recessions and anxious domestic populations also all too often resort to protectionism, worsening both their own economic circumstances and those of their neighbors. “There is already a turning inward, a search for autonomy and control of one’s own fate,” as former Indian national security adviser Shivshankar Menon put it recently. “We are headed for a poorer, meaner, and smaller world.”

Yet perhaps the main reason to hope for renewed international action is the sheer necessity of coordination. As the crisis rolls on, the disease will spread into more vulnerable societies, and those already battling outbreaks will move on to grappling with how to clamber back to some semblance of social and economic normality when virus is brought under control.

Moving toward a coronavirus vaccine clearly requires rapid international scientific collaboration. But beyond that, reopening and restoring international trade and travel networks will be impossible without wide-ranging agreements between dozens of governments, in part to ensure that resumed business activity does not lead to a resurgence in disease transmission.

The same is true for efforts to avoid a full-blown international financial crisis, as the initial domestic effects of the crisis continue to roil markets over the coming months. It is hard to see which parts of the global banking and corporate world will come under sustained pressure first, but any subsequent support or rescue plans will certainly be hobbled without careful international planning.

Over recent weeks a small handful of countries, including China and Singapore, managed to reduce domestic COVID-19 infections, only to see a spike in numbers as others returned from abroad. Their experience suggests that attempts to beat back the pandemic in any one country are unlikely to be successful if it continues to rage elsewhere. As that reality dawns, the hope is that faltering international efforts will quickly gather in strength. “This pandemic has proven that no country is an island, and we have to fight on together,” says Wang Huiyao. “So far this has not happened as many had hoped, but better late than never.”

Recommended Articles

-

KNA | Global trade, U.S.-China tensions, AI regulation

-

[Research Features] China’s role in a sustainable post-pandemic globalization

-

Wang Huiyao: China is not a threat to the international community - the world can benefit through China’s development

-

Wang Huiyao in dialogue with Lawrence H. Summers

-

CNBC | Trump's shake-up of the old world order sends shockwaves through Europe