Wang Huiyao: China’s economic priorities vs the US’ focus on security

SCMP | October 09 , 2021The two sides of Asia: China’s economic priorities vs the US’ focus on security

■ China wants to be at the heart of ‘Economic Asia’ and is seeking to join trade pacts, including the CPTPP, and shape the trade architecture of the region

■ The US, meanwhile, wants to uphold its centrality in ‘Security Asia’ by forging narrow alliances, and continues to fail to engage on trade

By Wang Huiyao | Founder of the Center for China and Globalization(CCG)

Back in 2012, Foreign Policy published an article headlined “A Tale of Two Asias” by two US analysts. It describes two contrasting Jekyll and Hyde sides of the continent.

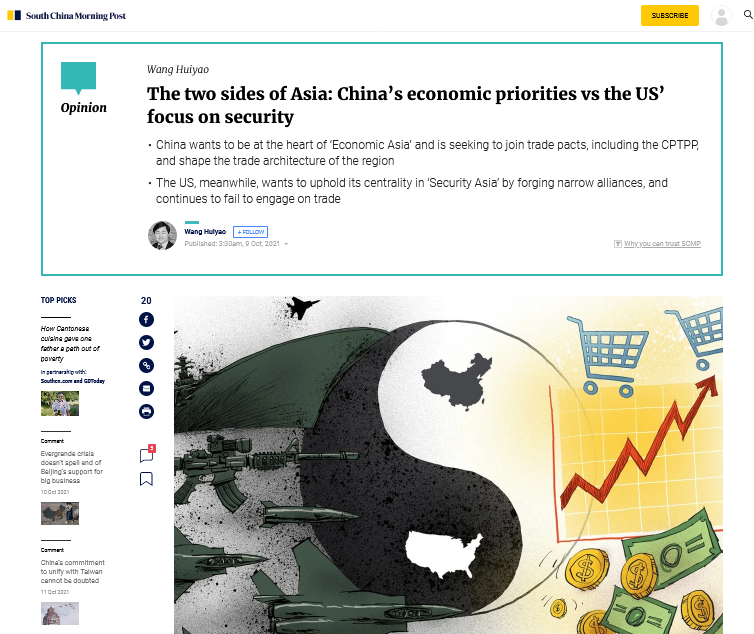

On the one hand, there is “Economic Asia”: a vibrant, integrated region with an economy now worth over US$30 trillion that is the most dynamic on Earth and an engine of global growth. On the other hand, there is “Security Asia” – a fractious and increasingly militarised region riven by mistrust, nationalism, historic antagonisms and territorial disputes.

It’s a crude dichotomy, but one that seems as relevant as ever.

Despite the pandemic, in many ways, it’s been a good few years for “Economic Asia”. The continent has become a locus of new multilateral initiatives, taking up the baton for free trade as progress stalls at the global level.

The share of intraregional trade in total Asian trade has grown to around 60 per cent, comparable to that in Europe. Last year, Asean overtook the European Union to become China’s top trading partner for the first time.

However, the spectre of “Security Asia” is never far away, at times threatening the economic progress that has helped to pull the region away from its troubled history. For example, Sino-Indian tensions played a part in India’s decision to drop out of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, or RCEP.

The ongoing spat between Seoul and Tokyo has hindered economic cooperation in East Asia, including negotiations for a trilateral China-Japan-Korea free trade agreement.

Recent events have again shown us the two faces of Asia. There was the first in-person summit of the Quad, a security-focused group consisting of the United States, Japan, India and Australia – states that have also stepped up joint naval exercises in the Indian Ocean.

This came just days after the unveiling of the Aukus security alliance which, despite having no Asian members, is clearly very much focused on the continent.

The week also saw a very different kind of announcement: China’s formal application to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership or CPTPP, the 11-member trade pact which, along with the RCEP, has been a recent bright spot for Asia’s economic integration.

These contrasting moves show how the US and China are strategically focused on the two different sides of Asia.

Put simply, China wants to be at the heart of “Economic Asia” and is actively trying to join free trade agreements and shape the trade architecture of the region, while building infrastructure to support trade and investment through the Belt and Road Initiative.

Conversely, the US has de-emphasised commercial policy – most notably by leaving the CPTPP’s predecessor, the Trans-Pacific Partnership – and instead seeks to uphold its centrality in “Security Asia” by forging narrow alliances to bolster its string of island bases.

Meanwhile, US economic involvement in Asia is waning in relative terms, and trade with the US is a diminishing share of total trade for most Asian countries.

As the authors of “A Tale of Two Asias” pointed out, economics and security do not run in parallel on the continent – indeed, they frequently seem to collide. But if there is tension between the two visions, surely it is “Economic Asia” that holds more promise for lasting stability and prosperity.

After the devastation of two world wars, Europeans recognised the need to bind their markets together to make war unthinkable. Economic integration offers a similar promise for Asia.

However, the dynamics of this process have always worked differently in Asia: integration is driven more by markets than governments, through the expansion of complex supply chains linking different countries.

In terms of development, political systems and social structures, the disparities in Asia are also much greater than in Europe. So, in the absence of strong regional institutions, flexible economic alliances like the CPTPP and RCEP are more suitable vehicles to gradually bind Asia, instead of rigid political and legal structures like the EU.

An enlarged CPTPP would be a huge boost to this vision for a unified and prosperous “Economic Asia”, bringing more of the continent under a formalised set of rules driven by multilateral consensus, and supporting growth and stability.

China’s entry would quadruple the CPTPP’s worldwide income gains, to US$632 billion a year, according to projections by the Peterson Institute for International Economics. Many members would stand to gain more than 1 per cent of their gross domestic product – a welcome boost on the long road to post-pandemic recovery.

More immediately, China’s application should help defuse geopolitical tensions in the region. It opens up new channels of dialogue with current members and sends a signal to concerned parties – such as Australia, Canada and Japan – that China is committed to opening up and focusing on economics rather than security matters.

For now, Washington’s regional policy seems wedded to “Security Asia”. President Joe Biden has reiterated that he does not support the US rejoining the Pacific trade pact – which in any case Congress remains opposed to.

This failure to engage on trade is a glaring hole in America’s Asia strategy. But if one day the winds change in Washington, there is a chance that parallel CPTPP accession negotiations could even become a vehicle to reconcile economic differences between China and the US.

In any case, China’s move towards the CPTPP could help reduce friction between the great powers by aligning China closer with progressive global trade norms.

For now, all this remains a long way off. In recent years, reforms have brought China closer to CPTPP standards, but significant gaps remain. Accession negotiations are bound to be long and arduous.

Nevertheless, China’s formal application to join the CPTPP is a major step forward for Asia on a positive path. In this tale of two Asias, it is economics that leads to a happy ending.

Recommended Articles

-

Wang Huiyao: The 21st-century order has outgrown 20th-century institutions

-

Wang Huiyao: Beyond Blocs-Europe and China will not align nor compete, but selectively cooperate

-

Wang Huiyao: Key lessons from China’s ascent over the past 25 years

-

Wang Huiyao: Key lessons from China’s ascent over the past 25 years

-

Wang Huiyao: China and Latin America: Partners in a shared new era