Why China should lead the mission to save the ailing WTO and reviving multilateralism

SCMP | November 27 , 2019The fate of the World Trade Organisation hangs in the balance. On December 10, just a single judge will be left on its Appellate Body as the terms of two remaining judges expire.

With the United States blocking new appointments, the world’s top trade court will be left short of the quorum required to hear appeals, effectively paralysing the WTO dispute settlement mechanism and undermining its defences against protectionism.

This demise comes when the global trading system is already fractious and vulnerable. A plan is needed to breathe life back into the WTO which, despite its faults, has underpinned growth for the past quarter of a century and remains the best vehicle for global trade liberalisation.

China, in particular, has benefited greatly since joining the WTO in 2001; now, the country should play a leading role in helping to reform and revive the organisation.

While the Appellate Body crisis is the most urgent malady afflicting the WTO, it is by no means the only one. For many years, the organisation has failed to keep up with important shifts in the global economy.

Its norms and rules are increasingly outdated for a world linked by complex value chains and growing digital and services trade.

While most members agree the WTO needs to be reformed, progress has been hindered by a lack of consensus and leadership. The United States, once a linchpin of the multilateral system, has become one of its biggest critics.

At this critical juncture, as the world’s largest trading nation and a leading advocate of multilateralism, China has an important role to play.

By working with other countries, it can take key steps to galvanise action and get the WTO back on the road to recovery.

At a critical moment for global trade, China can help save the WTO

First, China should work with a “coalition of the willing” and enact an emergency response plan to resuscitate the dispute settlement mechanism.

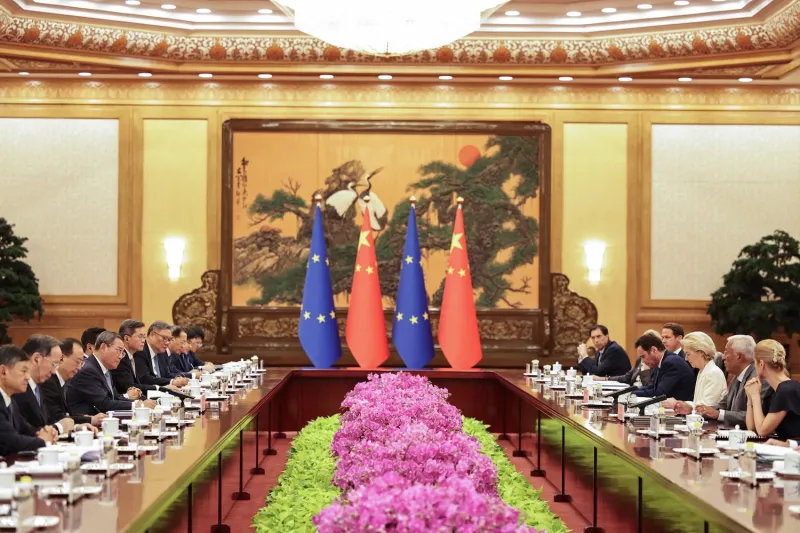

In particular, China can cooperate more closely with allied interests such as the European Union, Australia, Canada and Japan to explore solutions.

One possibility is to form an alternative mechanism via a plurilateral agreement: one that involves a group of countries rather than all members. This would restore the WTO’s ability to enforce rules while upholding its authority.

To facilitate this cooperation, China should strengthen communication with parties working to modernise the WTO. China has set up a joint working group with the EU for this purpose and could also establish a communication channel with the Canada-led Ottawa Group.

Blocking China’s blockchain push will leave the world worse off

The second principle is to focus on issues that can provide an “early harvest” to provide some momentum for the reform process. WTO talks have all but ground to a halt since the Doha Round died a quiet death in 2015. At present, fishery subsidies are the only item left on the agenda.

Rather than trying to tackle long-standing intractable problems from the current deadlocked state, issues should be prioritised where there is common ground to make breakthroughs and get the ball rolling.

One promising area is e-commerce, which plays an ever-growing role in global trade. China is one of 75 WTO members that launched talks on drawing up global e-commerce rules earlier this year. While some sticking points remain on data security and privacy, there is strong potential to make headway.

Drawing on its own experience and position as a major e-commerce player, China should play an active role in consultations with other members to make progress on rule-making for the digital economy.

Green issues could provide another potential win for WTO reform. Building on the consensus reached at the G20 earlier this year to tackle marine plastic pollution, China should spur multilateral action to meet these goals through the WTO. Shared environmental challenges such as plastic pollution can provide a useful impetus for reform.

The third area to address is how WTO members are categorised. The simplistic labelling of countries as “developed” or “developing” fails to capture the diversity within these categories.

Members self-designated as “developing” range from some of the world’s poorest countries to industrialised economies such as Singapore and South Korea.

Asia-Pacific needs the WTO to stay relevant in an uncertain world

While often not applied in practice, the “special and differential treatment” granted to developing countries has become a bone of contention in reform negotiations.

As a bridge between the developed and developing world, China could help to refine ways of classifying countries that reduce friction with industrialised members but protect reasonable allowances for developing countries.

Finding the right remedies and nursing the WTO back to strength will not easy. But while its condition is critical, it is by no means terminal.

Faced with the alternative of seeing our global trading system splinter under the forces of unilateralism and protectionism, every country should be eager to explore new ways to revive the WTO. As the world’s largest trading nation and a strong advocate of multilateralism, China has a significant role to play.

Recommended Articles

-

Wang Huiyao: Beyond Blocs-Europe and China will not align nor compete, but selectively cooperate

-

Wang Huiyao: Key lessons from China’s ascent over the past 25 years

-

Wang Huiyao: Key lessons from China’s ascent over the past 25 years

-

Wang Huiyao: China and Latin America: Partners in a shared new era

-

Wang Huiyao: Only a multipolar coalition can secure Ukraine peace